Condemned with Freedom

This essay delves into the sensitive topics of suicide, self-harm, and suicidal ideation. Please be cautious while reading, as these subjects may trigger trauma or negatively impact your mental state.

Following the tragic loss of several acquaintances to suicide, I became deeply engrossed in researching this distressing phenomenon. What I discovered was particularly alarming. South Korea, the country of my birth and upbringing, holds the unfortunate distinction of having the highest suicide rate among OECD nations. Even more disheartening, suicide stands as the leading cause of death for individuals in their 20s in this country. Being a Korean myself, I'm keenly aware of the cultural nuances that make discussing suicide a taboo. In Korean society, people often resort to euphemisms and indirect language when addressing this issue. Rather than plainly stating that someone "died by suicide," we tend to use phrases like "made an extreme decision." Nevertheless, mental health professionals emphasize the importance of openly acknowledging suicide as "suicide." By doing so, we can create an environment where individuals grappling with suicidal thoughts can emerge from the shadows and seek help without fear of societal stigma.

Introduction

Death has always been a deeply troubling subject for me. Initially, I thought that my contemplation of mortality was just a passing phase, one I would eventually outgrow. However, with the passage of time, it has become increasingly evident that it is a profound and enduring topic that I cannot ignore. Throughout my artistic journey, I have extensively explored the concept of duality and strived to visualize contrasting human impulses, a theme well-documented in my artworks and writings. Yet, I have never looked into how my interest with death, particularly self-inflicted death, has influenced my artistic practice. In this piece, I aim to share a contemporary exploration of suicide and how I have incorporated this knowledge into my creative works.

Following the summer exhibition, a large portion of my summer has been dedicated to submitting my work to various exhibition open calls. Initially, the task of submitting your work may seem straightforward, as you might believe you can reuse the same written materials and CV for each application. However, as an applicant, you quickly discover the necessity of continuously reworking and revising your essays for every application. It's an arduous undertaking, but the silver lining is that it unveils previously unexplored aspects of your own artistic practice. It's akin to watching the same movie multiple times and writing a fresh critique each time you view it.

Through the process of composing five distinct essays about the same artwork I've created, I've come to realize that my video "Clean Slate" defies simple categorization under a single theme. "Clean Slate" encapsulates a multifaceted narrative, touching upon the themes of belonging, self-discovery, the loss of a friend, the insecurities of a budding artist, and most significantly, the struggle to overcome self-destructive thoughts and ideation.

Condemned with Freedom

Following the summer exhibition, a large portion of my summer has been dedicated to submitting my work to various exhibition open calls. Initially, the task of submitting your work may seem straightforward, as you might believe you can reuse the same written materials and CV for each application. However, as an applicant, you quickly discover the necessity of continuously reworking and revising your essays for every application. It's an arduous undertaking, but the silver lining is that it unveils previously unexplored aspects of your own artistic practice. It's akin to watching the same movie multiple times and writing a fresh critique each time you view it.

Through the process of composing five distinct essays about the same artwork I've created, I've come to realize that my video "Clean Slate" defies simple categorization under a single theme. "Clean Slate" encapsulates a multifaceted narrative, touching upon the themes of belonging, self-discovery, the loss of a friend, the insecurities of a budding artist, and most significantly, the struggle to overcome self-destructive thoughts and ideation.

Condemned with Freedom

Thomas Joiner is a prominent psychologist and suicidologist who has modernized suicide theories. He introduced the "Interpersonal Theory of Suicide" to explain the causes of suicidal urges and how they lead to action. According to this theory, the main factors driving the desire for suicide are "Thwarted Belongingness" and "Perceived Burdensomeness." However, having these two factors alone does not necessarily result in lethal behavior. Individuals must also overcome the fear of death by acquiring the capability to harm themselves. In simple terms, only those with the capacity for self-harm, who also feel a lack of belonging and perceive themselves as burdensome to others, are more likely to die by suicide. It might seem odd to draw this theory like a form of a scientific equation, but it highlights the complexity of determining what suicide exactly is.

Diagram of Thomas Joiner’s “Interpersonal theory of suicide”

The term "suicide" is commonly defined as "the act of taking one's own life." Although the dictionary often emphasizes the intentionality of this act, determining true intent can be challenging, especially since less than one-third of individuals who die by suicide leave a suicide note. Additionally, when considering altruistic suicides, martyrdom, rational suicides, and assisted suicides, the traditional dictionary definition of suicide proves inadequate.

In his book "Le Suicide," French sociologist Emile Durkheim proposed four categories of suicides: egoistic, altruistic, anomic, and fatalistic. Durkheim believed that regardless of the type, all suicides are the result of a disrupted balance between the individual and society's regulations. He focused on two types of regulation: social integration and moral regulation. Egoistic and altruistic suicides occur when individuals fail to maintain an appropriate level of social integration. Too little integration can lead to egoistic suicide, while excessive integration may drive individuals to commit themselves to a larger societal goal, categorized as altruistic suicide.

Thomas Joiner's theory, as discussed in his book "Why People Die by Suicide," is influenced by Durkheim's ideas. For instance, "low social integration" aligns with Joiner's concept of "thwarted belongingness," while "high social integration" is akin to "perceived burdensomeness.”

These two concepts are prominently depicted in my film "Clean Slate." The film explores the protagonist's state of ambivalence regarding assimilation into society. His narrative illustrates the struggle to strike the right balance of integration. He desires to be a unique individual, but this triggers his fear of not fitting into society. Yet, when he tries to emulate those he admires, he is tormented by the realization that he might become a mere Simulacra of them.

A scene from “Clean Slate”

Narration: What if I’m a bad reproduction?

a bad mimicry of an original, irreplaceable, noble being?

YOUR SO CALLED “AESTHETIC OF YOURS”

IS A COMBINATION OF 5 ARTISTS OR ART MOVEMENTS

THAT ALREADY HAVE BEEN PRESENTED AND APPRECIATED!

YOU ARE JUST A REPRODUCTION,

NO A CHAOTIC, REDUCTIVE ABOMINATION OF

EVERYTHING GREAT THAT EXISTED BEFORE YOU!

In the play "Pygmalion" by George Bernard Shaw, Eliza Doolittle, a common flower girl, arrives at Higgins' house with a request – to teach her how to speak and behave like a lady. Her aspiration is to undergo a complete transformation, becoming refined enough to pass as a duchess. Despite Higgins' initial unsuccessful attempts to mold Eliza to his preferences, he eventually achieves his victory when Eliza successfully masquerades as a genuine lady at a grand ball. By Act 4, Eliza has indeed undergone a radical transformation, not only in her speech and mannerisms but also in her perception of herself. Unlike her initial eagerness to change, she now struggles with confusion about her new identity and who she has become.

A scene from the film adaptation of “Pygmalion”

Pygmalion (1938)

Eliza: I sold flowers. I didn't sell myself.

Now you've made a lady of me I'm not fit to sell anything else.

I wish you'd left me where you found me.

Jean-Paul Sartre famously stated that "man is condemned to be free," offering a perspective that echoes Kierkegaard's notion, albeit without religious connotations. It poses an intriguing irony. The pursuit of freedom is undertaken by individuals risking their lives, yet one could argue that defining freedom itself as a burden for existence appears paradoxical. My interpretation of Sartre's statement is that we possess an array of life choices, each accompanied by its unique consequences. Angst becomes inseparable from freedom, as humans are destined to have an endless vertigo of making the “right” decision.

"The Stanley Parable," a game written by Davey Wreden and William Pugh, has garnered acclaim as one of the most remarkable "meta" games of the 2010s. In this context, "meta" denotes self-awareness or a keen understanding of its own category, particularly within gaming and pop culture. "The Stanley Parable" achieves this meta quality by allowing players to subvert the game's rules and by being inherently self-referential.

In this game you are Stanley who works in a dull office serving your duty as a cog in the company. Doing meaningless task over and over, but you are not aware of your purpose. Stanley's existence takes a turn when a narrator intervenes, giving him instructions. Initially, as a player, you might feel a sense of purpose, but you soon realize that the narrator is the puppeteer, and you've been merely following their script.

This twist in the game serves as a witty meta joke – the brief illusion of free will as you rebel against being a cog, only to find yourself conforming to the narrator's directives once again. You can restart the game and explore hidden features within the game world. You have the option to defy the narrator's instructions, escape through a window, or even end Stanley's life by jumping from a second-story window. These actions are an attempt to assert your individuality, to refuse being Stanley. Yet, the irony lies in the fact that the very freedom you seek to exercise becomes your torment. No matter how hard you try, you remain ensnared, unable to escape the office or evade the narrator's influence.

Screen shots from “The Stanley Parable”

The feeling of entrapment puts the player in despair. You face a choice: continue seeking ways to circumvent the narrator and assert your individuality, or accept that these endeavors are ultimately meaningless and quit the game. If you decide to proceed, the narrator tantalizes you with a carrot – a yellow arrow labeled "The Stanley Parable Adventure Line," suggesting a happy ending if you follow it. Alternatively, the narrator might suddenly declare "You win!" However, the achievement feels hollow, devoid of genuine joy. What if you choose to quit? In a sense, this might be the equivalent to giving up on life if Stanley were a real, perceivable entity. Whether you quit or persevere, you come to the realization that the pursuit of "meaning" in your actions and decisions plays a significant role in your experience. The truth is that we are not inherently obligated to find or assign meaning to every decision we make, and we are born without a predetermined purpose.

“Sisyphus” painted by Franz Von Stuck

Sketch of my work “ How Do You Sleep at Night?”

Much like Sisyphus, condemned to eternally push a boulder uphill only to witness it roll down again, we often find ourselves trapped in a cycle of repetitive and seemingly meaningless tasks throughout our lives. The pursuit of purpose can seem elusive, and our lives are filled more with actions that lack significance than with truly meaningful endeavors. This may explain our relentless efforts to avoid making what we perceive as "wrong" decisions. However, as long as we cling to the belief that a single, ultimate decision will fulfill our desires, we risk feeling trapped and devoid of options, much like Stanley when he believes he has achieved a "meta" state.

In the context of my film, "Clean Slate," the protagonist finds himself in a situation similar to Stanley's. His narrow self-perception leads to feelings of defeat and shame, ultimately culminating in a sense of entrapment. Psychologist Rory O'Connor explains that this entrapment acts as a bridge, linking defeat and humiliation to thoughts of suicide. While the film's protagonist may not explicitly express suicidal ideation, he adopts a coping mechanism by deeming everything in his life unworthy – his social connections, cherished possessions, and even his body and soul.

A scene from “Clean Slate”

Narration: To be honest, there is nothing so dear to me,

there is nothing so important that I would regret losing.

There is no possession that I cherish and

I even believe that part of my body can be replaced.

Most things can be replaced.

I’m not only talking about tangible objects.

The subject that is replaceable also contains

immaterial concepts, emotions, and many more.

The

protagonist gives himself another chance, to make himself worthy enough to live. He believes that by becoming an individual, an original being, he can find the motivation to continue living.

In an experiment known as "Cognitive Consequences of Forced Compliance," conducted by social psychologists Leon Festinger and James M. Carlsmith, 60 Stanford students were tasked with performing a monotonous, repetitive activity of turning wooden pegs a quarter clockwise. Following this, they were divided into two groups. One group received one dollar, while the other group received 20 dollars, to lie about how enjoyable the task was to subsequent participants. After the experiment, both groups were interviewed about their true feelings. Surprisingly, the group that received only one dollar ended up believing the lie. They did so because they felt guilty about deceiving others for such a small sum, and they genuinely wanted to believe that their task held meaning. This example aligns with the self-deception described by existentialists.

The film's protagonist, in a similar vein, engages in self-deception, but in the opposite direction. He endeavors to convince himself that his artistic journey is meaningless because he believes he can never attain the level of greatness achieved by past artists. He deceives himself into thinking that his long-standing friendship lacks significance due to an insurmountable difference between them. Furthermore, he convinces himself that he can determine the purpose of his existence.

In an experiment known as "Cognitive Consequences of Forced Compliance," conducted by social psychologists Leon Festinger and James M. Carlsmith, 60 Stanford students were tasked with performing a monotonous, repetitive activity of turning wooden pegs a quarter clockwise. Following this, they were divided into two groups. One group received one dollar, while the other group received 20 dollars, to lie about how enjoyable the task was to subsequent participants. After the experiment, both groups were interviewed about their true feelings. Surprisingly, the group that received only one dollar ended up believing the lie. They did so because they felt guilty about deceiving others for such a small sum, and they genuinely wanted to believe that their task held meaning. This example aligns with the self-deception described by existentialists.

The film's protagonist, in a similar vein, engages in self-deception, but in the opposite direction. He endeavors to convince himself that his artistic journey is meaningless because he believes he can never attain the level of greatness achieved by past artists. He deceives himself into thinking that his long-standing friendship lacks significance due to an insurmountable difference between them. Furthermore, he convinces himself that he can determine the purpose of his existence.

Conclusion

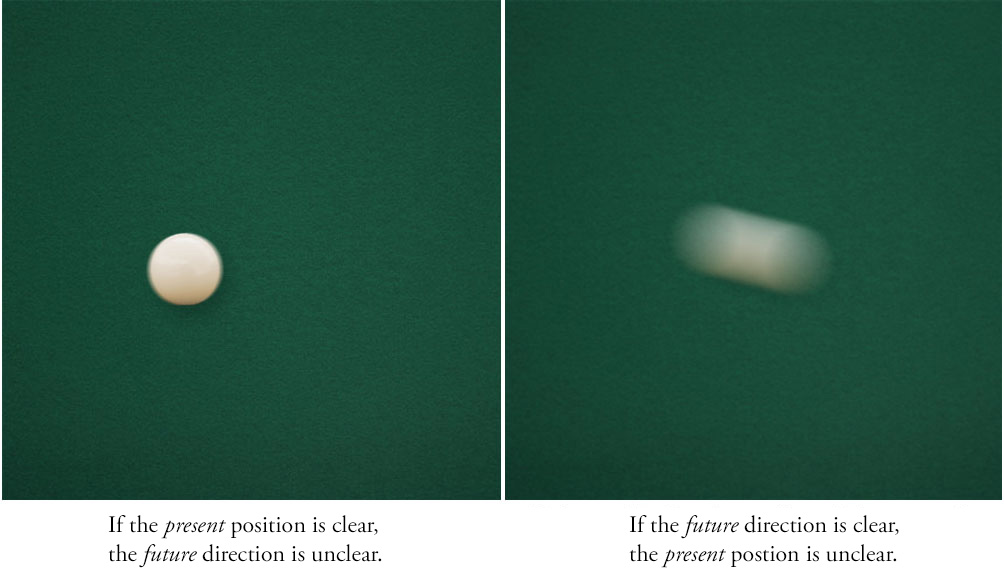

Making a decision means that you are setting the probability at 100 percent. When one remains undetermined, the probability can be near 100 percent but never exactly 100. What if the protagonist didn't decide that the purpose of his existence was to be an original human being? The probabilities would scatter to various other options. With too much freedom, an abundance of choices can at times feel like a curse. For instance, since the advent of social media, latent possibilities have become more visible, leading to questions like "what if I had chosen a different path?" When we are constantly reminded of how others are living and how their decisions have seemingly benefited them, it becomes challenging not to doubt our own choices. At times, we even experience regret and wish to live someone else's dream.

However, what if we reframe it like this? As the philosopher Martin Heidegger suggested, humans are thrown into this world; we exist as "Dasein," simply "being there." We exist in the present by making our own decisions. The protagonist's desire to be an "original being" represents the aspirations of many, a goal shared by countless individuals. Deciding that he will live a life that garners approval and adoration from others is an extreme choice, one that eliminates numerous possibilities. Moreover, this decision contains a significant flaw: it often entails projecting ourselves into a future where we fulfill our desires while neglecting the present and the process that leads to that future. One can always live in the present while leaving the future open-ended.

Now doesn't it sound more appealing to have numerous options? Wouldn't it be better to believe that we have the free will to live as authentic beings? In the end of "Clean Slate," the protagonist reaches a stage of acceptance. He acknowledges that he was trying too hard, transforming into a neurotic perfectionist. He accepts his imperfections and tells his friend, "I used to judge you for always changing your mind, but at least I think you were being true to yourself in every moment."

![]()

A scene from “Clean Slate”

Narration: Now I have a clean slate.

I lost so many parts of my life, being a coward.

Now I want to embrace how fragile and imperfect I am.

I am a people pleaser that acts so sly and timid to appease everyone.

I give up my beliefs if I can appease someone.

I’m arrogant and full of envy.

I used to judge you for always changing your mind,

but at least I think you were being true to yourself in every moment.

We often encounter familiar phrases so frequently that we cease to question them. Sayings like "Your life is a gift from God"(regardless of religious specificity) or "At least you have more freedom than those in worse conditions" are often met with indifference. I've always maintained skepticism toward such statements and found it unkind to use them in attempts to console individuals battling severe depression. It can feel as though these phrases limit one's freedom even to consider the option of ending their life. One common myth about suicide is that suppressing discussions related to it is the best approach. Paradoxically, allowing depressed individuals to share their thoughts about suicide and keeping the possibility open can deter them from taking such actions. Constricting their thoughts can have the opposite effect.

For anyone struggling with severe depression and suicidal thoughts, I hope they can challenge their preconceived notions. Just like the protagonist, perhaps we can liberate ourselves by questioning the societal rules imposed upon us. The protagonist realizes that being a simulacra can carry a different meaning if he so desires. By rejecting the preconceived notions of Plato's "Theory of Forms," he can assert that his work of art, too, can be celebrated as original. In the words of Max Demian from Herman Hesse's novel, we can become our authentic selves by breaking free from our shells.

The bird fights its way out of the egg.

The egg is the world. Who would be born must first destroy a world.

The bird flies to God. That God's name is Abraxas.

The message I intend to convey through this essay is not one of nihilism, such as "Humans are thrown into this world, I have no inherent purpose for existence," or "Everything is determined by probability, so my free will can't alter my life." I'm not advocating for perpetual nihilism. In fact, a touch of skepticism and nihilism about our perception and the world might be beneficial. However, I suggest that we employ that nihilism to uncover our authentic selves. Ironically, when one strives to be an original, unique being, they are more likely to be consumed by the mundane.

However, what if we reframe it like this? As the philosopher Martin Heidegger suggested, humans are thrown into this world; we exist as "Dasein," simply "being there." We exist in the present by making our own decisions. The protagonist's desire to be an "original being" represents the aspirations of many, a goal shared by countless individuals. Deciding that he will live a life that garners approval and adoration from others is an extreme choice, one that eliminates numerous possibilities. Moreover, this decision contains a significant flaw: it often entails projecting ourselves into a future where we fulfill our desires while neglecting the present and the process that leads to that future. One can always live in the present while leaving the future open-ended.

Now doesn't it sound more appealing to have numerous options? Wouldn't it be better to believe that we have the free will to live as authentic beings? In the end of "Clean Slate," the protagonist reaches a stage of acceptance. He acknowledges that he was trying too hard, transforming into a neurotic perfectionist. He accepts his imperfections and tells his friend, "I used to judge you for always changing your mind, but at least I think you were being true to yourself in every moment."

A scene from “Clean Slate”

Narration: Now I have a clean slate.

I lost so many parts of my life, being a coward.

Now I want to embrace how fragile and imperfect I am.

I am a people pleaser that acts so sly and timid to appease everyone.

I give up my beliefs if I can appease someone.

I’m arrogant and full of envy.

I used to judge you for always changing your mind,

but at least I think you were being true to yourself in every moment.

We often encounter familiar phrases so frequently that we cease to question them. Sayings like "Your life is a gift from God"(regardless of religious specificity) or "At least you have more freedom than those in worse conditions" are often met with indifference. I've always maintained skepticism toward such statements and found it unkind to use them in attempts to console individuals battling severe depression. It can feel as though these phrases limit one's freedom even to consider the option of ending their life. One common myth about suicide is that suppressing discussions related to it is the best approach. Paradoxically, allowing depressed individuals to share their thoughts about suicide and keeping the possibility open can deter them from taking such actions. Constricting their thoughts can have the opposite effect.

For anyone struggling with severe depression and suicidal thoughts, I hope they can challenge their preconceived notions. Just like the protagonist, perhaps we can liberate ourselves by questioning the societal rules imposed upon us. The protagonist realizes that being a simulacra can carry a different meaning if he so desires. By rejecting the preconceived notions of Plato's "Theory of Forms," he can assert that his work of art, too, can be celebrated as original. In the words of Max Demian from Herman Hesse's novel, we can become our authentic selves by breaking free from our shells.

The bird fights its way out of the egg.

The egg is the world. Who would be born must first destroy a world.

The bird flies to God. That God's name is Abraxas.

- Max Demian from Herman Hesse’s Demian

The message I intend to convey through this essay is not one of nihilism, such as "Humans are thrown into this world, I have no inherent purpose for existence," or "Everything is determined by probability, so my free will can't alter my life." I'm not advocating for perpetual nihilism. In fact, a touch of skepticism and nihilism about our perception and the world might be beneficial. However, I suggest that we employ that nihilism to uncover our authentic selves. Ironically, when one strives to be an original, unique being, they are more likely to be consumed by the mundane.